Back in 1992 in a bus station in the Chinese city of Wuhan, a baby was found alone. Someone picked up the little girl and brought her to the Wuhan Children Welfare House where she was named Xia Huasi.

At the time China was still under a strict one-child policy and families would be fined if they had too many children. There were no formal adoption processes in place that would let you give up children families didn't want.

Not long after Xia Huasi was found, a law was passed that allowed foreign nationals adopt Chinese babies. Margaret Cook, a school teacher from Massachusetts, came to China and picked up Xia Huasi and brought her home. She renamed her Jenna.

Jenna was happy with her mother, and was never really put off by the fact that she was adopted. "We would talk about adoption just like we would talk about what's for dinner. It never felt like something that was a big deal," she says.

Even though she loved her mom, there was always a part of her that wanted to know where she came from. "Most people are just born into the families they're born into and they never think twice about it. Whereas for adopted people there is always this possibility of another life," Jenna said.

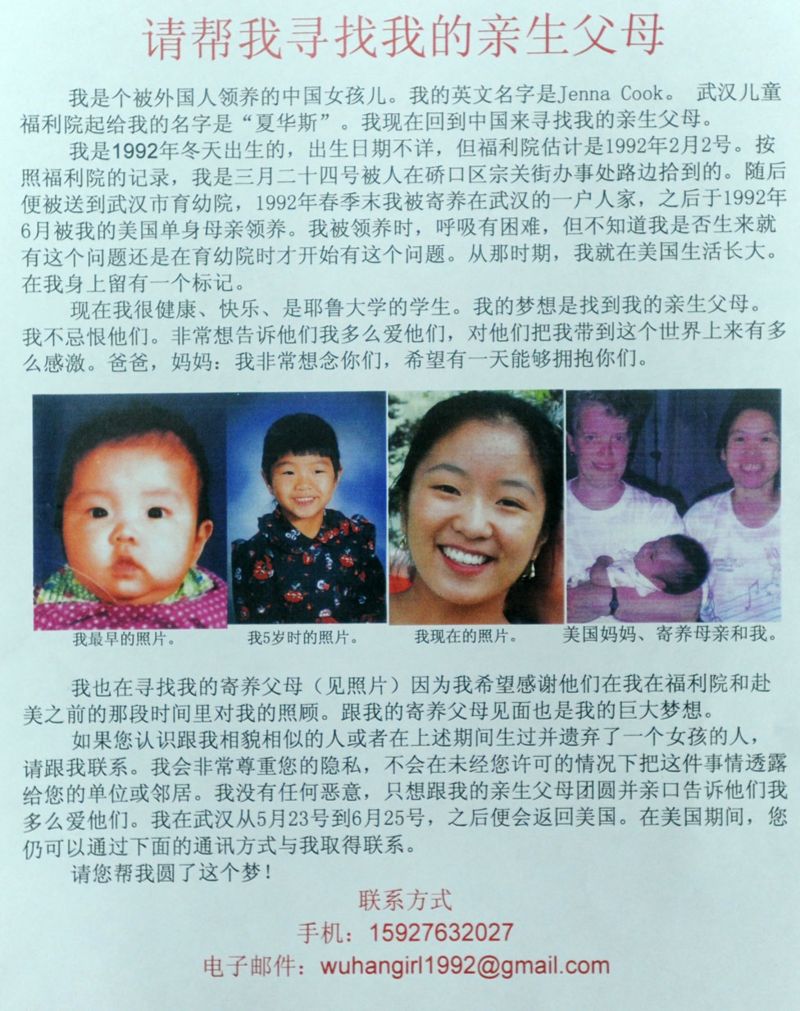

When she was 20 years old, she was given a grant to go to China and see if she could find her birth parents. She printed out flyers with pictures of her through the years on them and handed them out all over the town where she was from.

People would comment on it saying they may have known someone who gave up a child, or they knew someone in a similar situation, but it really took off when a local paper shared her story with the headline "Dad, Mom: I really hope that I can give you a hug. Thank you for bringing me into this world."

Responses started to flow in and she had to narrow it down before meeting the families. She eventually decided on 50 families to meet, each of them having left a baby on the same street in March 1992.

She was shocked by how many there were, and that they were willing to meet her. She said "Here are these people who have technically committed a crime and they're willing to come forward on national television. It was just unthinkable."

She was nervous meeting them, worries about what they would think of her. "I was really worried about what they would think of me. I was really worried that maybe I had done something wrong, and that was why they had abandoned me - I worried that they would be angry at me."

She met with all the families, and unfortunately none of them matched up. They ended up checking the DNA of 37 families to see if they were a match but none came up positive. It was heartbreaking for her to see these hopeful families, some of which had even held onto the fabric of the clothes to try to match it up.

Even though she didn't find her birth parents she doesn't regret the experience and thinks it helped her, "Before, there was always a small part of me that felt like there was something I could have done 20 years ago to have changed my fate and then I wouldn't have been relinquished by my family," she says. "But after meeting the birth parents I realized it was really out of my control."

If you want to hear more about her story she was on the BBC World Service Podcast and you can listen to it here.