A team of scientists at Stanford University have discovered a solution for combating cancerous tumors.

The newfound "vaccine," which used immune-stimulators to target tumors throughout the animal's body, has received promising results for the future of cancer treatment.

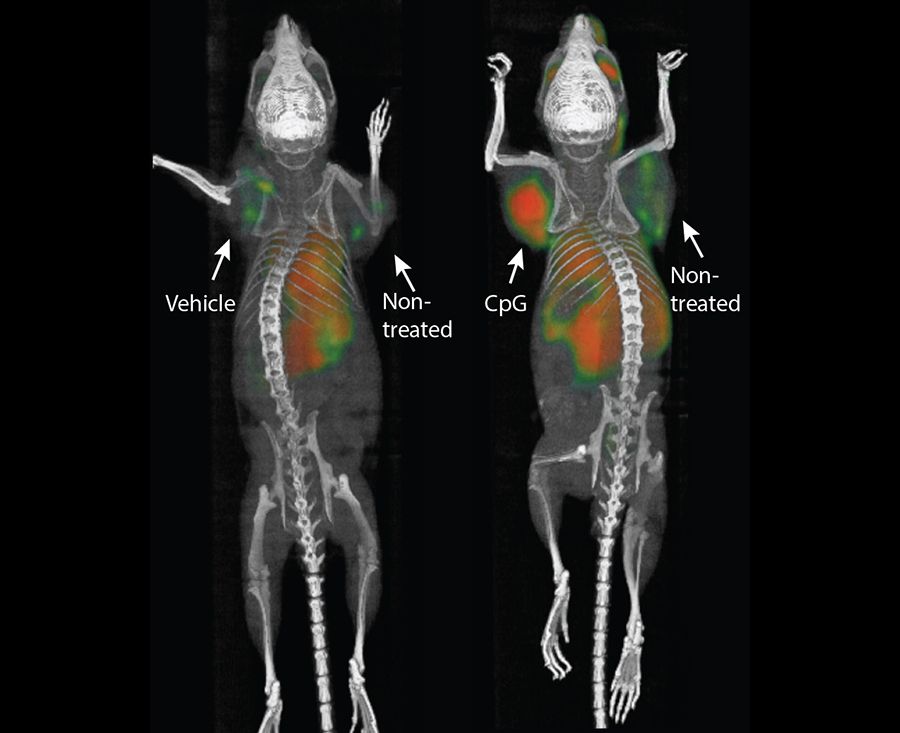

The university's research team said after they injected a combination of two immune boosters into the mice's tumors, all traces of the specifically targeted cancer had vanished from the rodent's entire body. This included metastases (a secondary malignant growth) that were previously untreated.

"When we use these two agents together, we see the elimination of tumors all over the body," Dr. Ronald Levy, the senior author of the study, told the Stanford Medicine News Center. "This approach bypasses the need to identify tumor-specific immune targets and doesn't require wholesale activation of the immune system or customization of a patient's immune cells."

Now, scientists are hoping the vaccine's success in mice will positively translate into the upcoming human trials.

In hopes that the vaccine will mimic the success it had on mice, Levy plans to recruit 15 individuals with low-grade lymphoma to be the first patients in the trial.

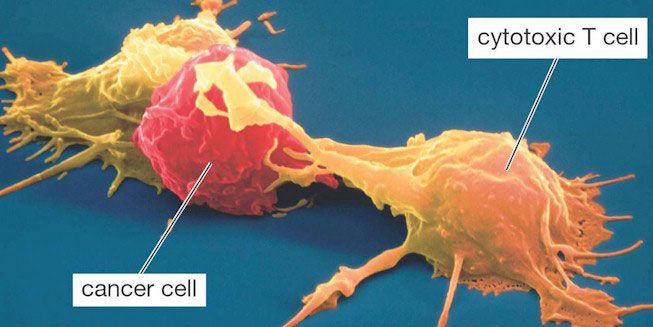

The scientist explained that when the immune system detects cancerous cells in the body, its cancer-fighting T cell will attack the tumor. Unfortunately, it will eventually be overpowered and the tumors will spread.

In the experiment, the T cells were regenerated after a microgram's worth of the two immune boosters were injected into a mouse's lymphoma tumor - thus giving the good cells the strength to fight off the cancer.

After the immune booster destroyed the tumor, they moved throughout the body to remove other lymphoma tumors plaguing the body.

Although the injection was successful in eliminating the targeted tumors present in the mouse, the T cells did not move on to a colon cancer tumor also found in the animal.

"This is a very targeted approach," Levy said. "Only the tumor that shares the protein targets displayed by the treated site is affected. We're attacking specific targets without having to identify exactly what proteins the T cells are recognizing."

However, while the vaccine was able to fight the lymphoma, it didn't treat the mouse's colon cancer.

The experiment tested 90 mice with cancer and had a 96.6% success rate in curing the rodents. In the 87 animals cured, only three had the cancer return, which was successfully treated with another round of vaccines. The treatment was also successful when it targeted breast, colon and melanoma tumors.

Levy claims that since the drug's application is localized, the treatment will be cost-efficient, and is unlikely to cause the same negative side-effects "often seen in other kinds of immune simulation." He also said the vaccine has the potential to work for several kinds of cancer.

"I don't think there's a limit to the type of tumor we could potentially treat as long as it has been infiltrated by the immune system," Levy said.

Are you hopeful for this new cancer treatment?